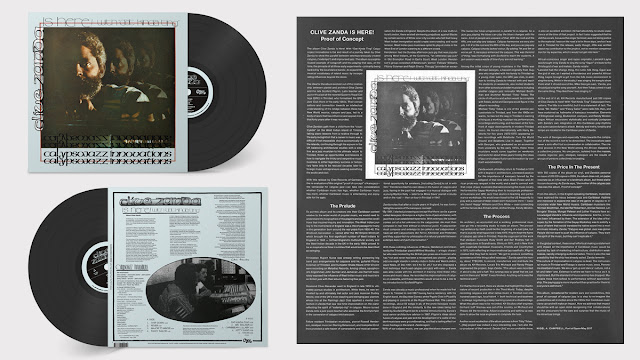

Liner Notes for the Clive Zanda vinyl album reissue on Cree Records (2017, CLP1220)

|

| 1965/66 QRC Jazz Club executive. Scofield Pilgrim, centre. was the founder and mentor. Photo courtesy Anton Doyle |

Clive Zanda’s path from a child from the “countryside” on the West Indian island of Trinidad taking piano lessons from a relative through to the early recognition that a career in music was a difficult if not impossible choice economically in the islands, continuing through his sojourn in the UK balancing architectural studies with a side line as a jazz musician to his ultimate return to Trinidad, threw up opportunities and lessons in how to navigate the tricky and serpentine music business to either legendary success or temporary fame only to be rescued decades later by foreign music entrepreneurs seeking something exotic and cool.

With this reissue by Cree Records of Germany, the re-evaluation of this original “proof of concept” of kaisojazz—the vernacular for calypso jazz—can take into consideration whether Caribbean music has legs, whether Caribbean music has merit, whether Caribbean music is entertaining and enjoyable for the ages.

THE PRELUDE:

To put this album and its creators into their Caribbean context relative to the wider world of popular music, we would need to understand the biographies of the players and explore the conditions that inspired inquiry and innovation. |

| HMT Empire Windrush |

The West Indian journey to the motherland of England was a rite of passage for many in the generation born around the war years from 1930-40. The Windrush Generation — named after the HMT Empire Windrush which brought the first significant number of West Indians to England in 1948 — birthed England’s multicultural society, and the West Indian decade in the UK in the early 1960s proved to be an inspirational time in a milieu that would soon be described as swinging.

|

| Rupert Nurse (1910–2001). Photo © 1992, Val Wilmer |

Desmond Clive Alexander went to England in late 1959 to ultimately pursue studies in architecture. While there, he was enthralled by and ultimately met actor and jazz musician Dudley Moore, one of the UK’s most dazzling and swinging jazz pianists whose trio at the Flamingo Jazz Club sparked a mental connection in Zanda that saw real time improvisation on the piano reflecting the spirit of “extempo-ing” in calypso. Moore turned Zanda onto a jazz piano teacher who would be the first lynchpin in the conversion of calypso into kaisojazz.

Fellow resident Trinidadian musicians, pianist Russell Henderson, steelpan musician Sterling Betancourt, and trumpeter Errol Ince provided a safe haven of camaraderie and musical conversation for Zanda in England. Despite the sheen of a new multicultural London, there existed simmering prejudices against Blacks by certain sectors of White inner-city London who felt that heavy West Indian immigration would create overcrowding and racial tension. West Indian jazz musicians opted to play at clubs in the West End of London catering to a different crowd.

Henderson had the Sunday afternoon jazz gig that was popular among West Indians, at the Coleherne, “an otherwise gay pub” in Old Brompton Road in Earl's Court, West London. Henderson’s group consisted of Betancourt, Vernon ‘Fellows’ Williams, Fitzroy Coleman and Ralph Cherry. This gig “provided an exceptional opportunity for amateurs, [including Zanda] to sit in with him.” Henderson had his own ideas on the fusion of calypso and jazz; in the past, he engaged in a musical dialogue with a young Wynton Kelly — later to be Miles Davis’ pianist in studio and on the road — then on tour in Trinidad in 1947.

Zanda notes that after a couple years in England, he was formulating his version of the kaisojazz concept:

“By 1961, I started pioneering a concept that there can be a genre called kaisojazz. Extempo is a higher form of jazz and kaiso; with jazz there is an established repertoire. With extempo, the subject comes out of a hat unknown to the calypsonian. He must then compose in real time without a reference point. A calypsonian must compose and extempo to be called a real calypsonian. I have sat with calypsonians like Terror, Kitchener and Pretender, and they supported my philosophy of a natural parallel between extempo kaiso and jazz improvisation.”With these colliding influences of Moore, Henderson and importantly the Trinidadian pianist Wilfred Woodley — a tragic character who was mocked by the British jazz press as a musician who has “not and never has been a recognised jazz pianist...playing odd one-night stands in smoky clubs in Soho and West London,” (Jazz News. 27 Dec 1961. Vol 5 No 52. p.6), but who displayed a fluid technique that fused calypso and jazz with ease — Zanda was able to curate with his architect-in-training mind these influences and music ideas. He recorded his improvisations of calypso on cassette, and these cassettes would prove to be a link to his introduction to Scofield Pilgrim.

Zanda was already a music professional when he made his first return to Trinidad in mid-1967 having had a residency with his English band, the Dez Alex Combo at the Pigalle Club in Picadilly and playing in concerts at the Royal Festival Hall. The cassette recordings, about 50 songs in all, of the proto-kaisojazz music done in England and the similarity to the new ideas being heralded by Scofield Pilgrim led to a formal introduction by Zanda’s local senior architecture advisor in 1967. Pilgrim's ideas about fusion of calypso and jazz and his development of a cadre of student musicians were ground-breaking and had a lasting effect on music heritage in the island. Zanda again:

“80% of our calypso music, one can play the blues changes over. The twelve-bar blues progression is parallel to a calypso. So, a jazz guy playing the blues can play the blues changes with the kaiso. A lot of people are unaware of that. With the root and the fifth, one can play any calypso. Calypso harmonies are very simple, I-III-V or the root and the fifth of the key, and you can play any calypso. Calypso chords lacked colour. By adding 7th and 9th or worse yet ♭5, kaisojazz enhanced the calypso. This was the kind of thing I was formalising with Scofield to teach the students. A jam session was a waste of time if you are not learning.”Among the initial corps of young musicians in the 1960s was Michael Georges, a bassist originally from Guyana who migrated with his family to Trinidad as a young child. Later, the QRC jazz club, in addition to inviting Zanda to interact with and teach the students on weekends, also invited students from other schools and older musicians including another calypso jazz innovator Michael Boothman and drummer Michael ‘Toby’ Tobas. The circle of influence and action would be complete with Tobas, as he and Georges would figure in the album's recording.

|

| Michael 'Toby' Tobas |

Michael ‘Toby’ Tobas is one of the premier percussionists in Trinidad, and from the 1960s onwards, he has led the way in Trinidad in earning a living as a working musician via performances, recordings and touring, and has been at the forefront of major developments in modern Trinidad music. He toured internationally with Harry Belafonte for five years (1972-1977) appearing on two recordings with Belafonte: Turn the World Around and Belafonte Live in Japan. Together with Georges, who graduated as an economist from university by the early 1970s, these three musicians would come together on weekends and work for about three years honing the ideas of jazz and calypso fusion and innovation by constant woodshedding.

Zanda would ultimately return to Trinidad in 1970 with a degree in architecture, a renewed passion for the importance of kaisojazz fanned by the zeitgeist of that time when Black Power and African pride was rampant in the world, and a zeal to connect with that corps of jazz musicians that were evolving the music locally. He formed the Gayap Workshop then to incorporate professional musicians and QRC Jazz Club alumni in teaching and performance workshops. He would even travel to the US frequently to play with several West Indian-born musicians there — bassists David ‘Happy’ Williams and Chris White — even connecting with his heroes like Ahmad Jamal, Archie Shepp, Randy Weston.

THE PROCESS:

|

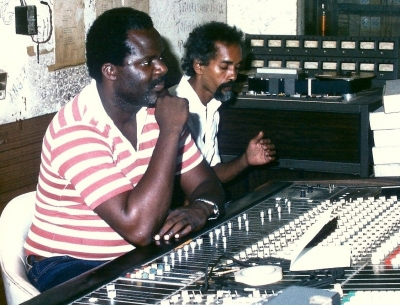

| In the studio, recording the album |

An architect, an economist and a working professional musician go into a recording studio to make an album. The preceding sentence by itself could be the beginning of a bad joke, but that is exactly what happened in late 1975. Pilgrim kept the flame of kaisojazz alive in Trinidad. Possibly cognizant of the work that steelpan musicians Rudy Smith and Earl Rodney had respectively done in Scandinavia, Otinku in 1971, and in New York with expatriate Caribbean musicians, Friends and Countrymen in 1973, both reflecting an improvisational jazz aesthetic, Pilgrim insisted that they had to record: “We got to produce something as evidence of this thing called kaisojazz.”

|

| Eric Michaud (left) |

Gerhard Nieckau: Recording Engineer

A peculiar aspect of this recording is that the original master tapes were kept by German recording engineer, Gerhard ‘Jeff’ Nieckau — he is referred to as “one of the prime movers of the plan to establish Trinidad & Tobago as an international recording entity.” (Billboard. Nov 20, 1976. p6.) — who released the track “Chip Down” on a CD compilation of in 2002, “his private archive.”

(Jeff Recordings: Rough Beats From Peru & Trinidad 1972-1976. Crippled Dick Hot Wax! - CDHW 084).

He states in that album's liner notes:

"Unfortunately the recording of the album ‘Calypso Jazz Innovations’ by CLIVE ZANDA was scheduled exactly for that time [late 1975 while Nieckau was in New York on business]. It could not be postponed...But with Clive, a highly intelligent teacher whom I worship, and Eric Michaud, a local sound engineer, I had worked hard in advance on all details of the recordings, such as setting up microphones and musicians, etc. Please forgive me for choosing a recording which is not 100% mine. Eric coped with this task very well, and at least I participated in planning the track ‘CHIP DOWN’, a hypnotic and monotonous jazz number, which I wouldn't want to do without."

—(My emphasis. Linernotes by Jeff: English. Jeff Recordings Microsite.)

Nieckau’s Tomba Music was cited by Billboard magazine around that time as being a music publisher for a number of significant music tracks and albums from the mid-late 1970s, including this album. (The album label erroneously states that Tomba Music owns the copyright. No documentation was found to corroborate this claim. Under Trinidad law, copyright can only be assigned by written document.)

Another recent recollection of the album process is from ‘Toby’ Tobas:

“...[the] project was indeed a very interesting one. I am also the co-producer of that record. Zander [sic] as you probably know, is also an excellent architect. He had absolutely no studio experience at the time of that project. In fact, I also suggested that he did the vocals, because the singer he hired, was not doing justice to the material. I was on the road a lot in those days, and so I was not in Trinidad for the release, sadly though, little was written about my contribution to the project, not to mention compensation for my expertise, which I would not get into here.”African-conscious singer and rapso originator, Lancelot Layne was brought in by Zanda to sing the song “Ogun” a tribute to the Orisha god of war and metals. Zanda recalls:

“Lancelot had the shango thing, the rustic folk thing. Ogun was the god of war, so I wanted a thunderous and powerful African thing. Layne brought a girl from the folk music environment to sing the song. While in the studio, I was singing the song to show them what it should sound like. Mike Georges said, ‘Zanda, you should just sing the song yourself.’ And then Tobas joined in said the same thing. They liked how I was singing it.”At the end of it all, KH Records manufactured just 350 copies of Clive Zanda Is Here! With “Dat Kinda Ting” Calypsojazz Innovations. The title is a mouthful, but it is a statement of fact. The tunes “Mr. Walker” and “Fancy Sailor” were radio hits then and have sustained as hallmarks of kaisojazz innovation. Elements of Ellington-ian swing, Dave Brubeck-ish cool jazz, and Randy Weston-esque African excursions stylistically and sonically juxtapose with Zanda’s own integration of Afro-Caribbean poly-rhythms and a percussive dynamic attack. Melody and metre, tonality and tempo are located in the Caribbean piano of Zanda.

The work of Georges and especially Tobas towards the completion of the record is not to be diminished. The innovations were never a solo effort but a conversation in collaboration. The creative process in the New World among the African diaspora is a collective process. No one person, isolated from the masses, creates legacies: jazz, steelpan, kaisojazz are the results of groups of persons collectively innovating.

THE PRIZE IN THE PRESENT:

With 350 copies of the album on vinyl, and Zanda’s personal re-issue of 200 CD copies in 2009 (at right), the album does not, on paper, resonate as an influencer or a landmark album, but those statistics are deceiving. As Zanda says, “the mother of the calypso jazz idea was this album. Proof of concept!”From this album, in the English-speaking Caribbean, musicians have explored the nexus between jazz and Caribbean rhythms and melodies to expand the idea of the genre of calypso to incorporate a wide range of New World music. Caribbean musicians like Michael Boothman, the late Raf Robertson, Annise Hadeed, Len ‘Boogsie’ Sharpe, Mungal Patesar and Luther François have acknowledged Zanda’s influence and importance. And he, in turn, has been influenced by them. The extension of the idea of kaisojazz by the formation of the Gayap Workshop was to solidify a base of talent that would translate the native sound into a modern music industry. Zanda: “Calypso was global. Jazz was global. People did not want to push the influence of calypso. They want the spirit of the music, but they can't replicate it.”

In the global context, these small efforts at making a statement with impact on the importance of Caribbean music would be stymied by lack of marketing infrastructure, distribution weaknesses, rapidly changing audience tastes. There is also the real possibility that the ship has already sailed. Zanda laments:

“The culture of improvisation in calypso is dead. The instrumental music in Trinidad and Tobago is dance music; soca, Panorama steelband music. We are a ‘get up and dance’ culture, not a ‘sit and listen’ one. Extempo is where we must focus as it is improvised. But the standard of musicianship has dropped. Musicians move from school to performance without apprenticeship. The paying gig is more important than practice for them to everyone’s detriment.”This album, remastered for modern ears and sensibilities, this proof of concept of calypso jazz is a step to re-imagine the possibilities set in motion since the 1950s that Caribbean musicians can and will make an impact. How we address that impact should be with an open mind recognising that collaborations are the precursors for the awe and surprise that the music of the Americas brings.

No comments:

Post a Comment