|

| Machel Montano and Etienne Charles. Photo © 2016, Che Kothari |

The trumpet’s evolution and positioning as the symbol of jazz has a heritage marked by iconic figures throughout its history. Icons like Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, and Wynton Marsalis represent a linear history. They also represent a shift from the working-class unschooled genius to the middle-class educated musician, who have paid their dues by apprenticeship. Charles, in this pantheon in the Caribbean context, represents the modern incarnation of the jazz musician taking his craft and skill to the world.

In the Caribbean, jazz does not have as high a profile as reggae, dancehall, calypso, or soca. Despite the region’s reputation for the once ubiquitous “jazz festival” — writer B.C. Pires noted back in 1993 that there were “more than 30 jazz festivals every year in the Caribbean and most Caribbean people have never been to one.” — these islands have not offered up many global stars in the modern jazz industry. Still, the most prolific modern recording artist in the Caribbean is Jamaican jazz pianist Monty Alexander, with over fifty albums released around the world. It’s also noteworthy that Caribbean music and musicians figure prominently in the genesis of jazz music in America. Charles carries on the tradition of regional jazz musicians who have fused their native cultural influences, rhythms, and melodies with aspects of jazz harmony and improvisation to create something new.

Jazz biographies love to dwell on the environment of upbringing of their subjects. Our cultural heroes have often been lauded for rising up and overcoming their hardscrabble ghetto existence. The Independence generation, certainly in Trinidad and Tobago, heard that education was key to the future: “you carry the future of Trinidad and Tobago in your school bags,” said Prime Minister Eric Williams in 1962. A middle-class lifestyle and existence were the goals of nation-builders. But our ongoing fascination with innate talent sometimes obviates intelligent endeavour.

Etienne Charles was born “early in the morning” in July 1983 into a middle-class family in Port of Spain, who later moved to a well-to-do neighbourhood in the west of the island. He excelled academically, sequentially graduating from the high school Fatima College, then with undergraduate and graduate degrees in music from Florida State University (FSU) and the Juilliard School in New York City — epitomising the intelligence and excellence needed by Caribbean people to compete in the modern global creative industries.

|

| Photo © 2017, Maria Nunes. |

Currently, Charles serves as associate professor of jazz trumpet at highly ranked Michigan State University (MSU), where he just completed his eighth year, and where he was awarded tenure in 2016. “I’ve definitely taken to academia,” he says, “and teaching is one of the most crucial professions in our society, with respect to inspiring as well as leading students through their exploration of idioms, styles, and techniques. It’s also something I find great joy in doing.” Charles is obviously well respected at MSU — he was awarded the 2016 Teacher-Scholar Award, which recognises some of the best teachers at the university. In the words of James Forger, dean of the College of Music, Charles is “one of the brightest minds in jazz performance and artistic creativity today.”

All this academic brilliance works in tandem with the other side of Etienne Charles. He is a professional musician whose profile has grown from its commercial beginnings as a teenager arranging horns for tropical rockers Orange Sky on their album Of Birds and Bees in 2002, through his debut album Culture Shock in 2006 and subsequent five albums, to his work as an arranger on two Grammy-nominated albums by René Marie, I Wanna Be Evil: With Love to Eartha Kitt and Sound of Red.

Recently, he’s been working as composer and arranger for modern jazz singers Somi and Joanna Pascale. “I enjoy writing and arranging for singers,” he says, “as there’s more to tap into for the arrangement: lyrical content, the tone of the vocalist’s instrument, phrasing, style, etc. It’s one of my secret passions. I’m a student of local and foreign arrangers Frankie Francis, Rupert Nurse, Earl Rodney, Johnny Mandel, Quincy Jones, Nelson Riddle, Frank Foster, Oliver Nelson, Leston Paul, Pelham Goddard, Art DeCoteau.” Calypso, jazz, and soca are all genres that feed his learning, and so inform his music.

This spirit of subliminal mentorship and apprenticeship was present from the beginnings of Charles’s recording career. The important Caribbean connections were not lost on him. “I had a bunch of heroes coming up, basically anyone who was playing music and took time to show me a line or tune. The Phase II Pan Groove crew, ‘Boogsie’, Annise ‘Halfers’ Hadeed, Dougie Redon, Lloyd ‘Bre’ Foster, Tony Woodroffe at the Brass Institute, Major Edouard Wade, who started me on trumpet lessons, Errol Ince, Kerry Roebuck, and Francis Pau at the National Youth Orchestra of T&T, percussionist Ernesto Garcia — those were my main mentors when I was growing up with a keen interest.”

All these “heroes” figured in Charles’s intellectual engagement with the traditions of jazz in his undergraduate years, as he was always aware of the responsibility to be true to his Caribbean roots.

Charles was confidently stepping out of his Caribbean comfort zone at twenty-three years old, just four years removed from his Trinidad existence, to explore both commercially and artistically the possibilities of jazz with his unique West Indian accent. The milestones were beginning to accumulate: he was already a National Trumpet Competition Jazz division winner in 2006, and he had performed at the North Sea Jazz Festival as part of the Florida State Jazz Combo in 2005.

As he was graduating from Florida State University in 2006, he was charting a career as a recording artist with the help of his teacher and mentor, renowned jazz pianist Marcus Roberts, widely known as one of the pre-eminent American jazz pianists of his generation. The resulting album, aptly titled Culture Shock, transcribed the musical diary of a newly minted artist and music immigrant in his New World of the United States. Jeremy Taylor, reviewing the album in Caribbean Beat, wrote that “Charles’s Caribbean roots show mainly in the opening and closing tracks . . . [and the] five central tracks wander rewardingly through blues and gospel and swing.” An audacious yet tentative debut, and a lesson learned; he needed more. There was no time to rest on his laurels.

“You carry the future of Trinidad and Tobago in your school bags.” The awe of learning in the capital of music, the Big Apple, beckoned. Charles enrolled in the Juilliard School in New York in the fall of 2006. “I think what might have been overwhelming to me when I got to Juilliard was the level of seriousness around me,” he recalls. “I’d never been in a place where everyone was not just talented, but so devoted to complete mastery of their craft.”

An attitude adjustment and a maturing in the world marked his graduation from Juilliard. An old Caribbean saying suggests that “common sense invent before book sense.” Charles, in America, recognised conveniently that the music business is a grand hustle. The hard-luck stories of chicanery and deceit suffered by musicians, a significant number being black and immigrant, are numerous and tragic — Bob Marley’s estate losing its case against Universal Music Group in 2010 over ownership of copyrights for his 1970s hit albums stands as a hallmark of exploitation — and Charles would not number in that league.

“Know the business, study it, get a mentor who knows the business,” is how he describes his modus operandi.

“Own your work, copyright your work, own the publishing, and own the masters. These were the words told to me by my mentors Ralph MacDonald and Marcus Roberts. Read contracts inside out and call a lawyer if you need. I have my lawyer on speed dial. Know that sacrifices must be made and investments must be made. What takes time normally costs money, and vice versa. Rome wasn’t built in a day, a talent isn’t honed in a week, and a brand isn’t built in a year. Be patient, humble, and persistent. Consistency beats intensity, always.”The creative process hardened by his years of collaboration and study at university resulted in a string of heralded albums from 2009 going forward, highlighting an evolved understanding of the place of the West Indian in the world. Charles befriended and was inspired by pioneering Trinidadian artist, dancer, and choreographer Geoffrey Holder and his larger-than-life oeuvre — “he proved before most others that we have something great in our islands” — so much so that Charles would not wince at the notion of tackling Caribbean music with an ear towards intellectual yet accessible enlightenment.

He organised his compositions and successive album productions around increasingly complex themes that unravel with maturing clarity.

“I’ve been focusing on writing within themes, as that’s how we shape the direction of our albums . . . I enjoy writing in this style because it allows me the process of research followed by synthesis and analysis, and subsequently composition. It gets me deep into the subject and out comes a longer piece. It also works well for thematic concert presentations.”

Folklore (2009) — described as “using the thematic structure of a suite of original compositions all based upon the mythologies and mythological characters of Charles’s Trinidadian/Afro-Caribbean heritage” — gives musical validation to the douen, la diablesse, soucouyant, and other characters in the lore of Caribbean slave narrative.

Kaiso (2011) reinterprets the songs of three legends of recorded calypso, the Roaring Lion, the Mighty Sparrow, and Lord Kitchener, as a testament to the idea that calypso music and the chantuelle’s canon are ripe for reinterpretation by jazz musicians worldwide. Thom Jurek of AllMusic wrote that Kaiso “examined calypso . . . through the lens of twenty-first-century post-bop. The end result expanded the reach of both musics without watering down either.”

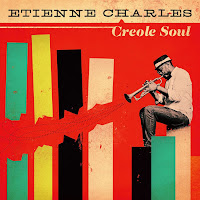

These two have been described as his “Trinidad” albums, because on his next project he widened his vision. The chart-topping Creole Soul (2013) bristled with a kind of energy that comes from realising that one has gone beyond the usual expectations of a Caribbean existence. Haitian kongo, mascaron, and bomba, and Martiniquan belair rhythms are explored in the context of a wider pan-Caribbean jazz. Covers of Bob Marley’s “Turn Your Lights Down Low” and Dawn Penn’s dancehall classic “You Don’t Love Me (No No No)” may suggest a fawning for popular uptake, but as Ben Ratliff of the New York Times puts it, the music on Creole Soul is also “intellectually sound, going deeper into Mr Charles’s basic interest, which is the affinities between Caribbean music and music from the American South, New Orleans jazz in particular. It doesn’t feel too academic or too grasping, overscripted or shallow. He’s got it about as right as he can.”

Critics were seeing parallels between Charles’s work and writer V.S. Naipaul’s early oeuvre. After Naipaul’s four “Trinidad” novels, he began to travel much like Charles did for Creole Soul, and again for his highly rated San José Suite in 2016. The possibilities for high accolades were obvious and forthcoming. Charles was written in to US Congressional Record for his “musical contributions to Trinidad & Tobago and the World” in 2012. His alma mater in Trinidad, Fatima College, inducted him in 2015 in its Inaugural Alumni Hall of Achievement as the youngest inductee.

He was invited to perform at high-calibre jazz festivals in the US (such as Newport, Monterey, and Atlanta) and internationally. He released the popular Creole Christmas album in 2015, transforming holiday classics and local favourites into a new creole jazz form.

But Etienne Charles the successful working musician and recording artist still has to balance his career with Etienne Charles the professor at MSU. “All in all, both teaching and scholarship are very important at MSU,” he explains. “So in addition to my teaching responsibilities in the College of Music, there’s also a significant research / composition / performance / grant-writing mandate to my appointment at the university.” That research and composition have yielded his most significant works to date, the aforementioned San José Suite and the forthcoming Carnival: The Sound of a People.

With the support of the Chamber Music America New Jazz Works Grant, funded by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, Charles was able to explore the broader traditions of creole cultural persistence in San José Suite. This ambitious work, based on research trips to three different New World places named San José — in California, Costa Rica, and St Joseph, Trinidad — dares to magnify the idea of the wider Americas as a crucible for the continuing assimilation and transformation of disparate musical influences. Taking in the stories and ideas of Native American heritage and the later African interlude, it presents the modern listener with an intelligent yet accessible understanding of who we are in the Americas.

More recently, the forthcoming Carnival suite — debuted live in Trinidad in 2017 and to be released on disc in 2018 — is the result of the award of a 2015 Guggenheim fellowship, which allowed Charles to research and explore the music of Trinidad and Tobago’s Carnivalesque processions, the Canboulay and J’Ouvert and other elements, to locate the musical response of Afro-Caribbean people to the circumstances of slavery, freedom, and colonialism.

Allied with this Carnival suite project was a new venture for re-introducing live brass band music on the road for Trinidad’s 2017 Carnival: We the People. “I have been studying this calypso/soca music for almost fifteen years steadily,” Charles says. “We the People was also a way to push the reset button with respect to how Carnival had been taken over by the pretty mas, and how most brass bands had been taken out of the equation. The fact remains that live music is a crucial element of real Carnival. Those who know, know! If we want our cultural and artistic aesthetics to survive and be passed on from generation to generation, they must not be viewed as ancient, outdated, or too expensive,” he goes on. “The ‘modern vs traditional’ debate must be addressed.”

Proud, influential and successful are words to describe our greatest creative artists. Add to that list young, intelligent and shrewd — and add Etienne Charles’s name to the growing pantheon.

- An edited version of this article appears in the July/August issue of Caribbean Beat as the cover story entitled "Etienne Charles: a head for jazz and a creole soul"

No comments:

Post a Comment